By Susie Coston, National Shelter Director

Three states — Minnesota, Wisconsin and now Iowa– have proclaimed a state of emergency, with millions of commercial birds believed to be infected by avian influenza. The death count is multiplying by the day and it’s estimated we’ll see 20 million birds destroyed overall as a result of the worst bird flu outbreak to strike the U.S. since the 1980s. Here’s what you need to know about this disease.

What is avian influenza?

Avian influenza (AI), or bird flu, refers to a number of viruses that infect birds. The viruses are classified as either low pathogenicity (LPAI), which causes a relatively mild illness, or high pathogenicity (HPAI), and results in severe illness.

Beginning in December 2014, HPAI was found in ducks in the Pacific Northwest, marking the first time in years that it had been detected in the U.S. Since then, multiple HPAI strains have infected flocks of domestic birds in multiple states. Strains H5N8 and H5N1 infected flocks on the West Coast, where the disease now appears to be dying down somewhat due to hot, dry conditions. Strain H5N2 is currently raging through the Midwest and making its way east.

The CDC reports that the strains of AI currently active in the U.S. pose a very low risk to humans. Among birds, however, they are highly contagious and in most cases fatal.

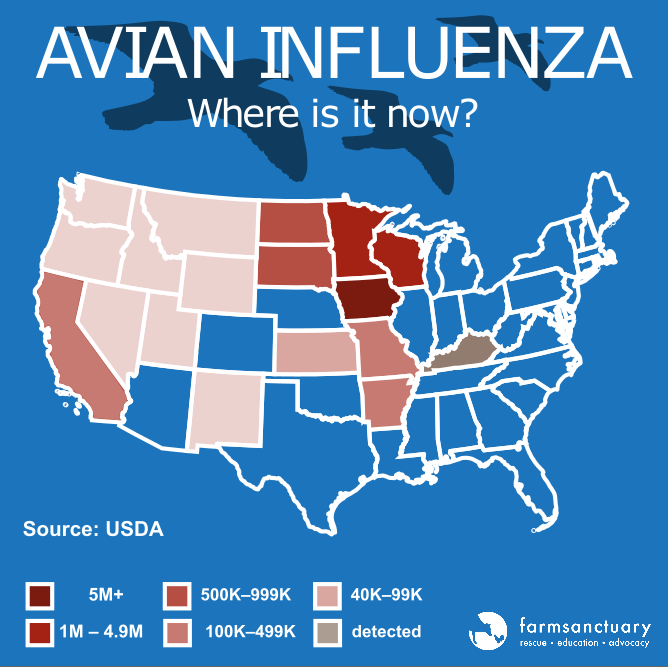

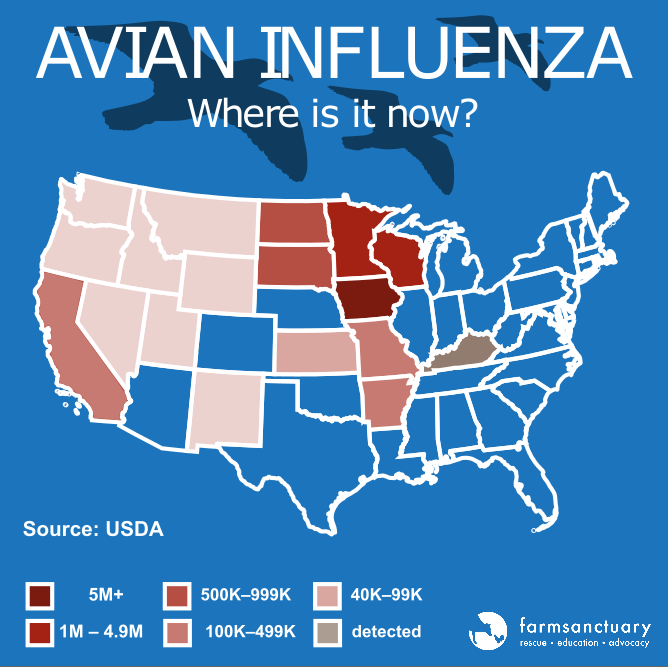

Where has AI spread?

Note: Detected refers to non-commercial findings. Estimates as of May 1, 2015.

As NPR reports, Minnesota has been hit hardest, with close to 50 flocks affected, but the disease has struck many other states as well.

Wherever the virus is found, USDA and state officials kill the entire flock in order to contain the disease. The standard culling method is to fill the housing buildings with a water-based foam that suffocates the birds to death.

The American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) designates this method as an appropriate means of “mass depopulation,” defined as “methods by which large numbers of animals must be destroyed quickly and efficiently with as much consideration given to the welfare of the animals as practicable, but where the circumstances and tasks facing those doing the depopulation are understood to be extenuating.” This endorsement tells you much less about the type of death delivered by the foam — which is undoubtedly horrid — than it does about the abysmal standards of welfare that pass as acceptable in an industry predicated on mass confinement and slaughter. By raising birds in groups of tens of thousands, or hundreds of thousands, or millions, producers create conditions in which humane euthanasia, or humane treatment of any sort for that matter, is impossible. The circumstances are “extenuating” by design.

In the U.S., more than 15.1 million domestic birds have been killed due to AI detections since the beginning of March 2015. Here’s a state-by-state breakdown of reported detections and cullings:

Minnesota: As of April 27, the virus has been detected in at least 46 turkey farms, and at least 2.7 million turkeys have been killed. The virus also has been detected in a facility raising chickens for meat and a laying hen facility, resulting in a total of over 500,000 chickens in Minnesota being killed. Additionally 150 turkeys belonging to a backyard flock were killed.

Iowa: There have been eight detections resulting in a total of almost 10 million deaths. At two turkey farms, a total of 61,000 turkeys were killed. At each of two egg facilities, 3.8 million hens were killed, and at another three egg facilities and a pullet farm a total of 2.3 million chickens were killed.

Wisconsin: There have been eight detections. At two egg facilities, a total of 980,000 chickens were killed. At five turkey facilities, 467,500 turkeys were killed. In a backyard flock, 40 mixed-breed chickens were killed.

South Dakota: AI was detected at six turkey farms, and 285,000 turkeys were killed.

North Dakota: AI was detected at two turkey farms. At the two facilities, 109,000 turkeys were killed. An additional 2,000 chickens also were killed at one of the facilities.

Arkansas: AI was detected at one turkey farm, where 40,000 turkeys were killed.

Missouri: AI was detected at two turkey farms, where 52,000 turkeys were killed.

Kansas: A low pathogenic strain of AI was detected in a commercial poultry facility in Kansas. The species and total number of birds affected were not released. An unknown number of ducks and chickens in a backyard flock also were killed.

California: There have been five detections including two wild ducks. At two turkey farms, 206,000 turkeys were killed (at one of these facilities, only a low-pathogenicity strain was found; nonetheless all of the facilities’ turkeys were killed). At one “broiler” chicken and duck facility, 114,000 birds were killed.

In addition to the states listed above, AI has been detected in the following states in wild migratory waterfowl, captive wild birds (such as falcons), and/or backyard flocks:

Idaho

Kansas

Montana

Nevada

New Mexico

Oregon

Utah

Washington

Wyoming

AI has also been found in Ontario and in British Columbia, where it was first detected in December 2014, before we were tracking the spread of the disease. The total number of birds affected at turkey and chicken facilities in British Columbia is reported to have been 250,000. In Ontario, the virus has been found in two turkey facilities and one facility raising chickens for meat with a total of 52,800 turkeys killed and 27,000 chickens killed.

Please check our Farm Animal Adoption Network (FAAN) Facebook page for updates. We continue to track new outbreaks. The disease is still spreading. This is an epidemic.

How has AI spread?

AI is spread in two ways: 1) directly from bird to bird, and 2) through contact with the manure of an infected bird. AI can be spread by equipment, vehicles, clothing, and other materials that have come into contact with the manure of infected birds. This includes, for instance, the shoes of someone who has walked by a lake where infected ducks have left droppings. (Additionally, some researchers have speculated that strong winds blowing infected debris into animal housing may have contributed to the broad reach of HPAI in Minnesota; however, biosecurity failures are still believed to be the primary cause of the Minnesota outbreak.)

The spread of the virus has been linked to wild migratory birds, especially ducks and geese. Typically asymptomatic, these birds are able to carry the disease from area to area and shed it in their droppings. In domestic birds, especially turkeys, HPAI induces a ghastly and highly lethal disease.

Why have so many birds died?

While the migrations of wild birds help account for the broad geographical reach of this epidemic, it is industrial farming practices that account for the staggering mortality. The reason 3.8 million birds fell victim to AI in a single Iowa facility is because there were 3.8 million birds in a single facility.

Keeping large numbers of animals together, especially in the intensely crowded conditions characteristic of factory farms, leaves those animals highly vulnerable to disease. (In fact, these conditions may even create breeding grounds for new strains of diseases. Learn more about factory farming and disease.)

Ironically, factory farm proponents have long cited biosecurity as a justification for keeping large numbers of animals confined in buildings with no outdoor access. As we’ve seen in this epidemic, biosecurity at these facilities is failing, and the confinement practices that ostensibly enable tight biosecurity are instead dooming millions of birds to disease and culling.

What is Farm Sanctuary doing to protect its shelter birds?

California

When HPAI appeared in California, we took immediate action to protect the birds at our shelters in Orland and Acton. We suspended visitor access to bird areas and instituted a “no birds in, no birds out” policy at both shelters. This means, unfortunately, that we cannot perform any bird rescues involving these locations while the HPAI risk remains high.

We have isolated our shelter birds from contaminants using tight-weave shade tarps, which keep wild fowl out of our bird areas and also prevent their feces from dropping into those areas as they fly over. We have also had to close off our ponds to the birds — ponds are the areas that pose the greatest risk of infection from wild waterfowl, who often land on open water to swim and eat.

All staff members at these shelters must now don special ISO gear and use foot baths when entering any bird area, and they are advised to change into different shoes upon entering the shelter in general from the outside, as an extra precaution. Additionally, all staff members are trained to identify signs of disease, both in our resident birds and in any wild birds in the area.

New York

As yet there have been no reported cases of HPAI east of Wisconsin, but it has reportedly been found in wild birds and/or backyard flocks. That said, the disease could spread further as waterfowl continue their spring migrations. We are following the movement of the disease closely and remain in constant contact with our vets. Currently, we are working with our avian vet at Cornell to review and update our AI protocols.

The Watkins Glen shelter has a large population of chickens, turkeys, ducks, and geese belonging to many distinct flocks that must be kept separate. Implementing the strict biosecurity measures necessary to protect them all from AI would be a massive effort. We want to allow the birds to have a semblance of the life they enjoy at our sanctuaries while still being safe from this disease.

We are dedicated to maintaining the strictest biosecurity at all of our shelters in the path of HPAI. These measures are crucial not only to safeguard our birds from disease but also to avoid giving the USDA any grounds for demanding that our shelter birds be culled if the epidemic continues to spread, worsen, or spread to other species.

Farmers have a strong economic incentive to protect their flocks, but for us this is personal. We know each turkey, each chicken, each duck, and each goose at our shelters as an individual with a name and a personality. They are our friends. The millions of deaths resulting from HPAI, like the billions of deaths resulting from the consumption of meat and eggs each year, are catastrophic. But HPAI also represents a catastrophe for each individual bird: the ultimate devastation of losing one’s life. To us, the cause of each bird in our care is urgent and worthy of our very best efforts.

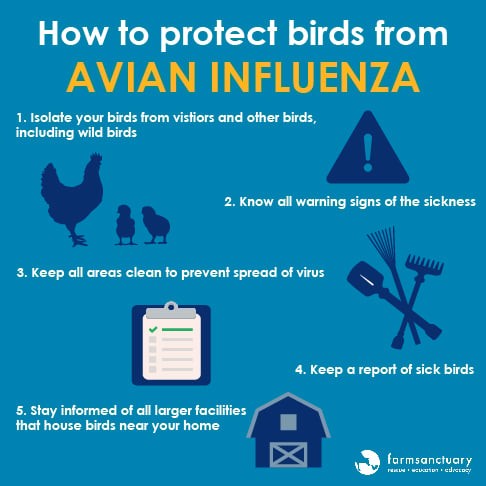

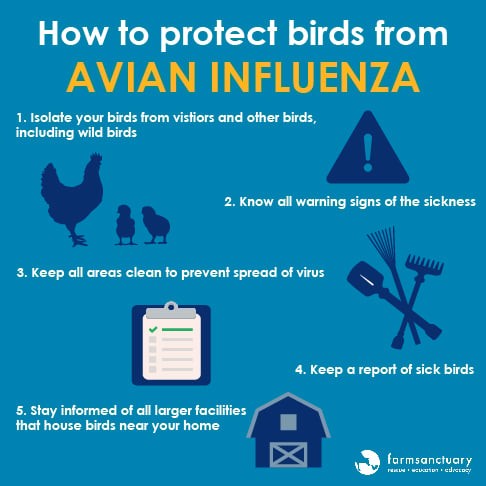

What Can I Do to Protect My Birds from AI?

We’ll say it again: This is an epidemic. Proper biosecurity is crucial for the protection of your own backyard flock and the birds in your area. If you care for any birds such as turkeys, chickens, ducks, or geese, please stay updated on the spread of the disease and be prepared to implement quarantine measures if it nears your area. You can check our FAAN Facebook page for the latest on AI outbreaks.

Read more on AI from the USDA.

* According to the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS), birds infected with AI may exhibit one or more of the following symptoms:

- sudden death without clinical signs

- lack of energy and appetite

- decreased egg production

- soft-shelled or misshapen eggs

- swelling of the head, eyelids, comb, wattles, and hocks

- purple discoloration of wattles, combs, and legs

- nasal discharge

- coughing and sneezing

- lack of coordination

- diarrhea

How can I help?

We’ve already incurred costs from securing our California shelters against avian influenza. If the disease nears our New York Shelter, the expense of protecting our birds there will be much greater. With your help, we can keep them safe. Please donate now.

We’ve already incurred costs from securing our California shelters against avian influenza. If the disease nears our New York Shelter, the expense of protecting our birds there will be much greater. With your help, we can keep them safe. Please donate now.